Red: The area of New England Joseph Smith grew up in and lived from 1805-1829; Blue: The area of New England Noah Webster grew up in and lived all his life 1774-1843

It was the changes in spelling and Americanization of pronunciation proposed by Webster in 1807 that has been retained, with few exceptions, even today and preferred by most Americans. In fact, he believed that “the New England style” of pronunciation was preferred by Americans rather than the affected elegance of the English theater. “On this continent,” Webster said, “the common man is the uncommon man,” basing his work on what the yeoman (common man) preferred and desired, he made it clear that the American common man was not the illiterate peasantry of England, but masters of their own persons, freeholders, and Lords of their own soil who could not only read and write and keep accounts, they had considerable education and read newspapers every week.

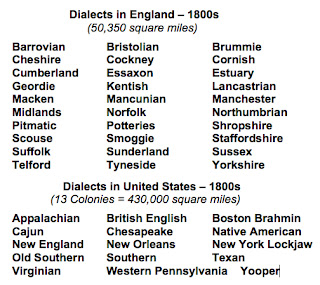

At the time of the Book of Mormon publication, England spoke 30 dialects of English in an area 50,350 square miles, while Americans spoke 15 dialects in the original 13 colonies and occupied lands covering an area of 430,000 square miles. Most Englanders found it difficult to understand one another, while most Americans could easily understand each other

"While in England, men separated by short distances struggled to understand one another because of various dialects, but in the extent of 1200 miles," Webster said, "Americans could universally understand one another." Coupled with his belief in God and acceptance of Jesus Christ, to which he often spoke and addressed his work, brought down upon him the judgments of Harvard and the Boston professional community, which eventually led him to move to Amherst, Massachusetts. He supported with great vigor the George Washington administration, was a member of the Connecticut General Assembly for nine sessions, member of the General Court of Massachusetts Legislature, was Director of the Hampshire Bible Society and Vice-President of the Hampshire and Hampden Agricultural Society, and helped secure permanent school funds in Connecticut and Massachusetts.

Webster later founded Amherst College in 1821, and while finishing his monumental American Dictionary at Cambridge in 1825, found no English publisher interested in his scholarly work. It was only in 1827, after putting up most of the cost himself, that he found an American publisher for his work in which he added 12,000 words to the largest dictionary known at the time. His dictionary traced the primary etymological meanings first in which he traced the origin of every word and through the various branches and meanings.

It was the German “Iron Chancellor” Otto van Bismarck who later ruefully remarked that “the most significant event of the 20th Century will be the fact that the North Americans speak English.”

Obviously, it cannot be said that the language Joseph used in transcribing his translation was that of the 1500s and 1600s, which was “defunct” in his day.

3. Use of 131 instances of fully consistent expressions, identical non-biblical citations from elsewhere in the text.

Let me answer this in this way. The commissioning of the King James Bible took place in January 1604 at the Hampton Court Conference outside of London, where king James called a conference. While the conference was a failure it lent emphasis for the need of an English Bible. James worked out a compromise between the Church and the Puritans, and appointed fifty-four learned men, who were to secure the suggestions of all competent persons, that, as the king put it, “our said translation may have the help and furtherance of all our principal learned men within this our kingdom.” He laid out 15 instructions to the translators. While only forty-seven of the men appointed are known to have engaged in it, they were divided into six companies of 7 or 8 men each, two groups at Westminster, two at Cambridge, and two at Oxford, with each group given a portion of the Bible, i.e., the books were divided between the groups. Vigorous effort did not actually get started until 1607, and when the translators had finished their assigned work, a copy of their work was sent by each group from the three locations to London.

The public received the first folio in 1611, and later that year the New Testament was printed and in 1612 the first complete Bible appeared. This "Authorized Version" never was authorized by royal proclamation, by order of Council, by act of Parliament or by vote of Convocation. Whether the words "appointed to be read in churches" were used by order of the editors, or by the will of the printer, is unknown. The original manuscripts of this work are wholly lost, no trace of them having been discovered since about 1655. On the other hand, it was not until 1661, that the Epistles and the Gospels in the Prayer Book, were changed, the authorized text superseding that of the Bishops' Bible. The Psalms in the Prayer Book, from the "Bible of largest volume in English," have not been superseded to this day.

Thus, the King James Version, which most of us use, was highly regarded, but was not an easy sell—it took herculean effort and more than a single generation before it finally came into the hands of most Englanders, and now most of the English-speaking Christian World. However, when you have 47 men working on the same project, each with powerful personalities, knowledge, beliefs and abilities, you are going to have some errors and problems. One can find numerous errors within its pages, erroneous doctrine and even inaccurate history; however, it is, overall, the Bible we use “as long as it is translated correctly.”

Now we have an individual and his team who are re-writing or revising the Book of Mormon through his Critical Text Project. While once again, I am not criticizing the work of these scholars and their efforts, it needs to be pointed out that man, in and of himself, is simply not capable of rewriting scripture based on modern knowledge, linguistics, and academics.

Take, for instance, the numerous cases where Skousen wants to replant words because he does not agree with the ones used in the original scribal text. First of all, Skousen makes a big point that Oliver Cowdery, though a teacher of his day, did not know as much as we might think he did and because of this, many times inserted or wrote down the wrong word because of his lack of knowledge and understanding.

At the same time, it needs to be pointed out that Skousen’s approach seems to leave a lot to be desired. In his lectures on his work, which film can be found on the internet of his discussions verbatim. In going over some of the words that are wrong in the record according to Skousen, a few here are listed to show the inaccuracy of his approach and findings:

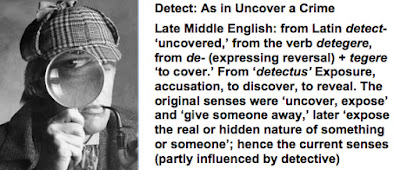

1) Detect. Skousen claims this word is inaccurately used in Helaman 9:17: “And now behold, we will detect this man, and he shall confess his fault and make known unto us the true murderer of this judge.”

Skousen claims the word should not be ”detect,” but should have been “expose” and proposed changing the text since he claims in this case detect is a 1500-1600s word and was archaic in 1829 at the time of the translation and would be the wrong word to use.

However,

in checking Webster’s 1828 American

Dictionary of the English Language, which lists the words used in New

England in the early 1800s, which we have already pointed out is a list of

words in use in New England during Joseph Smith’s time, the word “detect” meant

to “uncover,” hence, to “discover,” and that “detect” was a word specifically used

to “discover secret crimes and artifices.” As Webster wrote: “We detect a

thief, we detect what is concealed, especially concealed by design.” Even

today, the word means “to discover or catch a person in the performance of some

act.”

However,

in checking Webster’s 1828 American

Dictionary of the English Language, which lists the words used in New

England in the early 1800s, which we have already pointed out is a list of

words in use in New England during Joseph Smith’s time, the word “detect” meant

to “uncover,” hence, to “discover,” and that “detect” was a word specifically used

to “discover secret crimes and artifices.” As Webster wrote: “We detect a

thief, we detect what is concealed, especially concealed by design.” Even

today, the word means “to discover or catch a person in the performance of some

act.”Thus, the scripture could read correctly “And now behold, we will uncover this man and discover his secrets, and he shall confess his fault and make known unto us the true murderer of this judge.”

On the other hand, the word "expose" that Skousen wants to use meant, in 1828, from the Latin meaning "to place," or "throw or thrust down." It conveyed the understanding of "making bare," "to remove from that which guards or protects," "to lay open to attack," "to lay open to censure," "to make liable," "to put in danger," etc., which is not the same meaning at all. Even today, "expose" means "to make something visible," "leave something uncovered," "make or leave someone open to attack." None of which correctly conveys the meaning of the passage in Helaman 9:17. It might also be noted, that even today, the word "detect" means "to discover or investigate a crime or its perpetrators," "to discern something barely perceptible," "to discover or catch a person in the performance of some act."

Obviously, then, there is no error in the use of the original “detect,” the correct word was used by Joseph Smith and written down by the scribe—Skousen is in error since the word “detect,” unlike “expose,” applied specifically to uncovering the concealment of the secrets regarding crimes and criminals—the meaning of the passage in Helaman regarding the murder of the chief judge by the Gadianton Robbers. It was not just the right word, it was the perfect word—and the correct word of Joseph Smith's day.

(See the next post, “The Critical Text Project or Webster’s 1828 Dictionary: An Interesting Comparison-PtVI,” for more of the reader’s comments and our responses, and information about Royal Skousen’s project and Webster’s monumental dictionary, as well as comparing several words Skousen wants to change with their meaning and usage in Joseph Smith's time)

No comments:

Post a Comment