Continuing from the last posts

showing the fallacy of the Mesoamerican Theorists’ view of the Isthmus of

Tehuantepec in being the narrow neck of land—it becomes clear that this isthmus

is the real Achilles heel of every Mesoamerican model. In pursuing this, the

following is from John E. Clark, himself a Mesoamericanist and follower of John

L. Sorenson’s model, in which he defends the Mesoamerican Theory.

Clark’s arguments continue:

14. “The description of poisonous

snakes blocking passage to the land southward in Jaredite times is one of the

more unusual claims in the Book of Mormon. I agree with Warr that the incident

indicates warm climes and favors the interpretation of the narrow neck as an

isthmus rather than a corridor. Beyond this, there is not much that we can

wring from this description. John Tvedtnes suggests that the snakes could have

been associated with drought and infestations of small rodents,

something that could have occurred in either area. Poisonous snakes are

probably prevalent in both proposed areas. For now, this criterion does not

favor either proposal. For his part, Allen reads these passages metaphorically

to refer to secret societies; he claims that a literal reading is nonsensical.”

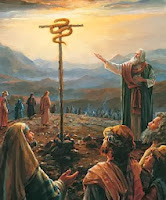

Response: First of

all, the Children of Israel were being bitten and killed by a huge number of snakes, so many in fact, that they infested the tens of thousands of Israelites in the wilderness (Numbers 21:6), which should suggest that the Lord has used snakes for his purposes more than just in the Book of Mormon. Secondly, a warm clime would fit Mesoamerica, the Rivas Isthmus, and also the Bay of

Guayaquil in Ecuador, South America (nearer the Equator than the other two), so that idea is not helpful

for a location. Secondly, there is nothing about the event that suggests an

isthmus over a corridor. However, the word isthmus (defined as “a narrow strip

of land with sea on either side, forming a link between two larger areas of

land”) certainly seems to be more accurate than corridor; however, since this

narrow neck of land had a “narrow passage” (Mormon 2:29), a synonym of corridor

is passage, but not pass, which this area is also called by Mormon (Alma 50:34,

52:9). So why don’t we stick with Mormon’s term “neck of land,” rather than

inserting Isthmus, especially since Mesoamericanists and James Warr both prefer

that term because their models are called an Isthmus (of Tehuantepec and of

Rivas).

As for “one of the

most unusual claims,” perhaps we should consider the purpose of this

action—it kept the Jaredites from entering the Land Southward (Ether 9:32-33).

Evidently, the Lord did not intend for the people to do so, and the snakes were

his way of keeping the Jaredites in the Land Northward “but that they

should hedge up the way that the people

could not pass” (Ether 9:33). And as for “John

Tvedtnes suggests that the snakes could have been associated with drought and

infestations of small rodents,” certainly this was because of drought,

since their was “a great dearth upon the land, and the inhabitants began to be

destroyed exceedingly fast because of the dearth, for there was no rain upon

the face of the earth” (Ether 9:30). Since a dearth is a lack of something, and

there was no rain upon the land, one would normally consider that a drought. And

with a lack of rain, this usually leads to a lack of food crops, so there was a

famine. This is not rocket science, and John Tvedtnes making the statement that

“the snakes could have been associated with a drought,” and Clark even quoting

that, seems on the ridiculous side. Certainly the idea of rodents, since there

is no mention or suggestion of such in the scriptural record, is equally

ridiculous to bring up. But as long as it was brought up, one of the favorite

meals of large snakes is small rodents, so it is not likely they would have

escaped the horde of snakes, and meaningless to bring up. The point is, it is

not wisdom to invent ideas not specifically mentioned or suggested by the

scriptural record—it does nothing for the student of the scriptures, and often

creates a false knowledge that serves little or no purpose.

15. “A careful reading of [Ether 9:35] may cause

questions to arise. Neither serpents nor flocks behave in the manner described

here. That is, poisonous serpents do not pursue animals; they defend themselves

against intruders including animals.”

Response: The key

here is the term: “The Lord did cause the serpents that they should pursue them

no more” (Ether 9:33), which should suggest that the Lord caused the serpents

to pursue them in the first place. Most importantly, we need to understand that

neither Mormon nor Joseph Smith used the term snakes, but serpents. A serpent

is a large snake, and if large enough, many animals would move away from them.

If the serpents were inclined to attack, an attitude that could have been

installed in them by the Lord, the animals would have fled. This brings to mind

when “the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people and they bit the people”

and the Lord told Moses hold up the pole with a brass serpent on

it (Numbers 21:8). It seems to me that there are no questions that need arise.

We need to trust in the prophets who wrote the scriptural record, and know that

nothing is too difficult for the Lord (Jeremiah 32:27).

16. “Additionally, if

in reality the flocks represent sheep or cattle, it is contrary to the way

these animals react. They simply do not travel hundreds of miles just to get

away from snakes…If the serpents and flocks represent groups of people instead

of animals, the scripture in Ether 9:31 takes on an entirely different meaning.

The poisonous serpents may be symbolic of the secret combinations, which did

"poison many people" (Ether 9:31). This is exactly how secret

combinations work. They spread their deadly poison among the people. They draw

them away by false promises for the sole purpose of obtaining power over the

masses and to get gain. Hence, the flocks could represent a righteous group of

people who retreated to the Land Southward to escape the wickedness that had

come upon the land. The word "flocks" is used in many instances in

the scriptures to represent a righteous group of people. Indeed, the Savior is

the Good Shepherd who watches over His flocks (Alma 5:59 60).”

Response: This is

very imaginative and reminds me of types of Sunday School discussions that

stray far afield of the scripture under discussion. On the other hand, most

scripture is symbolic and meant to point one toward Christ. Unfortunately, that

is no interpretation in the scriptural record to suggest such a meaning. And certainly the fiery serpents

mentioned in Numbers was tied directly into the pole and serpent Moses held up,

since the pole and serpent, when looked upon, saved the people, which is an

obvious suggestion of how looking upon Christ, the one that was lifted up on

the cross, results in our salvation. In this quote Clark attributes to Joseph

Allen’s book, evidently Clark and I agree since he goes on to state: “There is no indication in the

text that this verse should be read metaphorically to refer to secret

combinations.” In addition, we might consider that the Lord, who controls all things, evidently wanted flocks, herds, etc., to enter into the Land Southward during Jaredite times, so they would multiply and cover the Land Southward for the future needs of the Lehi Colony and the Nephite nation. It is always amazing when people start limiting what the Lord can and does do to further his plans.

17. “In discussions of

Nephite demography…it is now commonplace to make the observation that Lehites

and Mulekites were not alone on the continent. The same was true for the

Jaredites.”

Response: It is certainly commonplace among those who

champion Mesoamerica as the Land of Promise site. However, and once again,

since there is not a single reference of any kind in the scriptural record that

the Land of Promise was occupied by anyone other than Lehi’s family, the

Jaredites before them, and the Mulekites, it seems less than prudent to keep

harping on the unfounded belief that the area described in the Book of Mormon

was occupied by anyone between the Flood rescinding and the coming of the

Jaredites and later the Lehi colony. Those who do so sound like the proverbial "used-car salesman" of an earlier era who kept telling tall tales about his product that eventually the customer believed him. Such an approach falls under the also proverbial statement that come out of World War II, "if you tell a lie often enough it will be believed." There simply were no other people in the Land of Promise according to all the prophets who wrote about their land. Of course, it is completely self-serving

for Mesoamericanists to keep claiming this.

(See the next post,

“The Narrow Neck of Land One More Time – Part XIII—Mesoaermicanists’ Achilles

Heel,” for more on this difficult area for the Mesoamerican Theorist model to

reconcile with the scripture)